Flickr/B Rosen

Flickr/B Rosen

The doctor on call advised him to take the newborn away from its mother, when Pouya Jamshidi, a resident in Weill Cornell Medical College, delivered his baby.

The baby, a set of lungs and a healthy woman with mocha-pink skin, has been quarantined.

In the middle of the pregnancy, her mom had come down with tuberculosis. She’d contracted the lung infection and the disease came back despite preventative antibiotics and regular screenings. The reason: a favorite herbal supplement called St. John’s wort.

“The problem is most people don’t believe it a medicine since you don’t need a prescription for it, and so she did not inform us,” Jamshidi advised Business Insider.

St. John’s wort is now among the most common herbal supplements sold in the United States. But in 2000, the National Institutes of Health published a study showing that St. John’s wort could severely curb the effectiveness of several important pharmaceutical drugs — including antidepressants, birth control, and antiretrovirals for ailments like HIV — by speeding up their own breakdown within the human body.

“It basically overmetabolized the antibiotics so that they weren’t within her machine in the appropriate dose,” Jamshidi stated.

The findings on St. John’s wort motivated the US Food and Drug Administration to warn doctors concerning the herbal treatment. But that did little to stem public consumption or sale of it. Over the previous two decades, US poison-control centres have gotten about 275,000 accounts — roughly one every 24 minutes– of people who reacted badly to supplements; some of these were around herbal remedies like St. John’s wort.

Overdosing to a ‘natural’ supplement

The FDA defines supplements as products “meant to add further nutritional value to (supplement) the diet.” They are not regulated as drugs when a supplement is proven to cause substantial injury is it known as unsafe.

Half of all adult participants in a poll in the mid-2000s said that they took at least one supplement daily — nearly the exact same percentage of Americans who took both years ago. However research has found that the pills and powders to be unsuccessful and dangerous.

Reuters

Reuters

“Consumers should expect nothing from [supplements] because we do not have any obvious evidence that they’re valuable, and they should be leery that they may be placing themselves in danger,” S. Bryn Austin, a professor of behavioral sciences in the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health, advised Business Insider. “Whether it’s on the jar or not, there can be ingredients in there that can do harm.”

Despite many these warnings, the supplement industry’s marketplace is as much as $37 billion a year, according to one estimate. Ads for supplements are found on social media, in magazine pages, on internet pop-up webpages, also on TV. They are offered in corner health shops, stores, and big grocery conglomerates.

But supplements don’t come with explicit directions on how much to consume a dose that is suggested — or even drug interactions. Jamshidi’s patient had no idea she was putting that of her baby or her life .

But she was not alone. Utilizing information from 2004 to 2013, the authors of a 2016 study printed in the New England Journal of Medicine estimated that 23,005 emergency-room visits a year were connected to supplements. Between 2000 and 2012, the yearly rate of negative reactions to supplements — or “ailments” as they are understood in scientific parlance — rose from 3.5 to 9.3 cases per 100,000 people, a 166% growth.

During that period of time, 34 people died as a result of using supplements, according to a 2017 study printed in the Journal of Medical Toxicology. Six of those deaths caused from ephedra, the hottest weight loss supplement banned by the FDA in 2004, and three people died from homeopathic remedies. 1 man died after having yohimbe, an herbal supplement used for weight loss and erectile dysfunction. (Certain formulas of it can be prescribed to treat erectile dysfunction.)

‘You do not know what you’re dealing with’

Jamshidi said if he was feeling tired or tired, he used to have a multivitamin and had tried an herbal formula. But he remembers the moment he became cautious when began coughing up phlegm.

“She had been an incredibly cooperative patient, super participated and always showing up on time because of her visits, carrying all of our directions carefully — just a excellent patient,” Jamshidi stated.

Business Insider / Skye Gould

Business Insider / Skye Gould

They asked if she had started any new medications when his group and Jamshidi realized their patient’s tuberculosis was rear. She said no, but the following day she arrived in the clinic with a little jar of St. John’s wort.

She said she had been taking the herbal treatment for depression’s feelings she experienced after her pregnancy. Even though some tiny studies originally indicated St. John’s wort may have advantages for people with depressive symptoms, the NIH researchers failed to find enough evidence to support that.

Jamshidi’s patient needed to be isolated to guarantee the infection did not spread. She spent the past three months of her pregnancy.

“It was miserable — she was isolated for all that time, and then she couldn’t even hold the infant” Jamshidi stated.

In his opinion, one reason lots of individuals wind up in emergency rooms after taking supplements is that the quantities of active ingredients in them are able to fluctuate radically. A 2013 study printed in the journal BMC Medicine found that doses of ingredients in supplements may even vary from pill to pill — which poses a significant hurdle for doctors seeking to treat a negative reaction.

“There are other medicines that could have unwanted effects, however, patients come in and tell you that the dose, and you’re able to reverse it,” Jamshidi stated. “But with supplements, you do not know what you’re managing.”

‘Vitamines’ to prevent disease

By obeying the earliest “vitamine” in 1912, the Polish chemist Casimir Funk unwittingly unleashed a frenzy amongst chemists to produce or synthesize vitamins in the lab.

Between 1929 and 1943, 10 Nobel Prizes were given for work in vitamin research. From the mid-1950s, scientists also had synthesized 12 of the 13 essential vitamins. All these were added to foods like cereal, bread, and milkthat were offered as “fortified.” Foods that lost nutrients through processing obtained these sugars inserted back in and were labeled “enriched.”

A 1917 poster from the US Department of Agriculture advertised the ability to “increase vitamins” in your home. Library of Congress

A 1917 poster from the US Department of Agriculture advertised the ability to “increase vitamins” in your home. Library of Congress

They had been presented to deal with deficiencies that caused disorders like scurvy and rickets when supplements were introduced in the 1930s and 1940s. They were also seen as a means to prevent difficult-to-access and costly medical treatment.

In recent decades, though, a new production of nutritional supplements has emerged targeting primarily wealthy and middle-class women. These formulas ooze using all the lifestyle styles of 2017: minimalism (“Everything you need and nothing you do not!”) , bright colors, “fresh eating,” and personalization.

The celebrity Gwyneth Paltrow’s new lineup of $90 monthly vitamin packs — released through her controversial health company, Goop — have appealing names like “Why Am I So Effing Tired” and “High School Genes.” They promise to deliver health benefits like energy boosts and metabolism jump-starts.

“What is different about that which Goop provides is that the combinations, the protocols put together, were done by doctors in Goop’s team,” Alejandro Junger, a cardiologist who helped design a number of Goop’s multivitamin packs, advised Business Insider.

But a look at the ingredients in “Why Are I Effing Tired,” which Junger assisted design, suggests the formula is not based on rigorous science. The vitamin packs comprise 12.5 mg of vitamin B6 — about 960 percent of the recommended daily allowance — and ingredients like chamomile extract and Chinese yam, whose consequences haven’t been studied in people and for which no conventional daily allowance is present.

Goop

Goop

According to the Mayo Clinic, vitamin B6 is more “probably safe” from the recommended daily intake level: 1.3 mg for people ages 19-50. But taking a lot of the supplement has been connected with abnormal heart rhythms, decreased muscle tone, also preventing asthma. The Mayo Clinic notes high levels of B6 can also cause drops in blood pressure, also can interact with drugs like Advil, Motrin, and individuals prescribed for anxiety and Alzheimer’s.

“Individuals using any medications should check the package insert and speak with a qualified healthcare practitioner, including a pharmacist, about possible interactions,” that the Mayo Clinic’s site says.

Gwyneth Paltrow, the proprietor of Goop. Mario Anzuoni / Reuters

Gwyneth Paltrow, the proprietor of Goop. Mario Anzuoni / Reuters

Junger failed to comment on specific ingredients in the formula but said that many of these were added to “address the most common nutrient-mineral deficiencies of now: B, D, C, and E vitamins, potassium, calcium, molybdenum, amongst others.”

Other shiny new powders and pills that have materialized in recent months include a single called Ritualthat arrives at your doorstep in a white-and-yellow box combined with the words “The future of vitamins is clear.”

A month’s supply of this capsules that are glasslike — stuffed with tiny white beads prices $30. But the pills do not differ considerably more than your regular, more affordable multivitamin — that they have similar amounts of potassium, vitamin, folate, vitamin B12, iron, boron, vitamin E, vitamin and vitamin D.

VitaMe, another brand new supplement manufacturer, ships personalized daily packets with titles like “Good Hair Day” and “Bridal Boost” in a box resembling a tea-bag dispenser monthly for $40.

Its website says: “Our mission is summit nourishment. Delivered.” But its ingredients do not differ from those from conventional vitamins.

One of Ritual’s supplements. Ritual

One of Ritual’s supplements. Ritual

When vitamins can not rescue us from ourselves

No matter messaging or how brilliant their packaging, all these supplements fall prey to precisely the issue: We don’t need them to become healthy.

“We use sugars as insurance policies against whatever else we might (or might not) be ingesting, as if by atoning for our additional nutritional sins, vitamins can save us from ourselves,” Catherine Price, a science writer, writes from the book “Vitamania.”

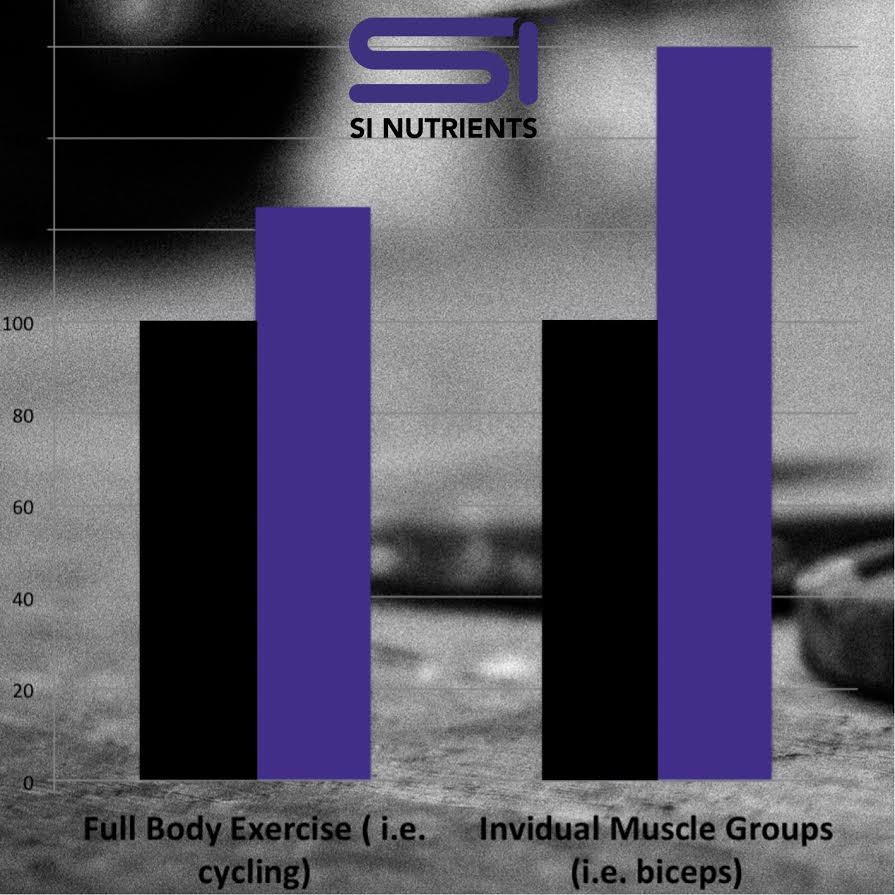

A sizable recent study published in the Annals of Internal Medicine looked at 27 trials of vitamins involving more than 400,000 people. The researchers reasoned that people who took vitamins did not survive longer or consume fewer cases of cardiovascular disease or cancer than people who did not take them.

Another study printed in the Journal of the American Medical Association in May divided nearly 6,000 men and gave them either a placebo or one of four supplements known for their brain-protecting skills. The results showed no decreased incidence of dementia one of any of those supplement-taking groups.

Study after study has also found that many popular supplements can cause harm. A large, long-term study of male smokers found that people who regularly took vitamin A were more likely to have lung cancer than those who did not. And a 2007 review of trials of several kinds of antioxidant supplements use it this way: “Treatment with beta carotene, vitamin A, and vitamin E may increase mortality.”

Risks research has indicated that our bodies are far designed to process minerals and the vitamins in whole foods . When we bite into a hot cherry or even a Brussels sprout that is crispy, we’re ingesting dozens of nourishment, including carotenoids, as well as phytochemicals like isothiocyanates.

Austin explained that’s why “nutritionists recommend people get their nourishment from whole foods, not matters that have been packed and place into a box.”

Flickr/With Wind

Flickr/With Wind

Where’s the FDA regulation?

After spending the past couple of months of her pregnancy and the first couple of weeks of her new child’s existence in isolation, the patient of Jamshidi was able to return and be with her family. Jamshidi explained that the experience changed the way he thought about nutritional supplements.

“I feel very negatively about these, and that I did not feel this way going to it,” he explained.

Request Steven Tave, the manager of the office of dietary supplement programs in the FDA, why the agency is not quitting more similar scenarios, and he will provide a simple answer: “We’re doing the very best we can.”

In 1994, Congress passed a controversial law called the Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act. Tave explained that until DSHEA passed, the FDA had been starting to govern supplements more stringently, the way that it does pharmaceutical drugs, but becoming “pushback in the industry.” The legislation forced the agency to be lenient.

The company has to apply for FDA approval, before a new drug can be sold, and the agency must conclude that the medication is safe and does what it claims to do.

“If the medication says, you understand, ’employed to treat cancer,’ then the agency’s reviewers will look at it and make a determination that there’s evidence that it does cure cancer,” Tave stated.

New supplements do not confront any burden of proof. The agency can review products that add new dietary ingredients when it gets a notification, Tave explained, however, it doesn’t “have the capacity to prevent anything from happening to market.”

The statement made sense, Tave stated, when DSHEA was passed. In 1994, about 600 supplement companies produced about 4,000 products for a total revenue of about $4 billion. But that market has ballooned — now, close to 6,000 companies pump out about 75,000 goods.

“We’re regulating that using 26 people and a budget of about $ 5 million,” Tave stated.

Eliminating a nutritional supplement calls for centers and boils down to documented emergency-room visits. Only when a supplement is reported to be unsafe as a consequence of one of these “adverse events,” as the FDA calls them, would be that the agency compelled to act.

“The majority of the time, we do not know a product is on the market until we find something bad about it from an adverse-event report. It is a very different regime from if we know what’s out there and we know what’s inside,” Tave explained, adding: “We do not want to be responsive. We want to be proactive. But we can not be.”

‘Consumers have no way to know’

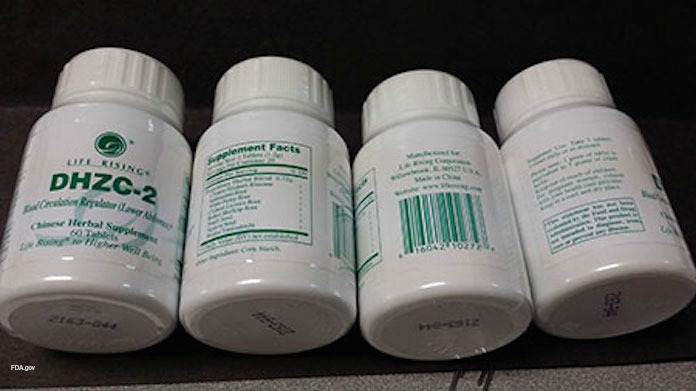

Most supplements are found to contain ingredients that are not listed on their labels — generally, all these are pharmaceutical drugs, a few of which are banned from the FDA.

A analysis of product recalls printed in 2013 in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that of these 274 supplements remembered from the FDA between 2009 and 2012, all contained banned drugs. A 2014 report found that more than two-thirds of those supplements purchased six months after being remembered still contained banned drugs.

“The products we see now have gone far beyond that sort of center group that they were in 1994,” Tave stated. “Now they’re marketed for all kinds of items — a few are long term, some are short term, several are compounds no one’s ever noticed before. It is a much different universe than it was at the time.”

Austin says three categories of supplements are the “most populous of the sector”: bodily improvement, weight loss, and sexual performance.

“Some of these businesses will not identify ingredients that they intentionally put in the goods,” she explained. “Some weight loss drugs, as an example, that have been pulled from the marketplace — we can still find them in the jar even though they do not put it to the label.”

The government workers looking into these issues, Tave’s 26-person team, did not even have a workplace until about a year and a half.

“We’re pretty sure were not aware of everything that’s on the market, but we do what we can,” he explained. “We all can do is apply the law.”

Supplements that are dangerous continue to seep through the cracks.

Flickr/Steve Depolo

Flickr/Steve Depolo

In 2016, the world’s largest supplement maker, GNC Holdings Inc., consented to pay $2.25 million to prevent federal prosecution over allegations that it sold a performance-enhancing supplement that claimed to increase speed, power, and endurance using an active ingredient called dimethylamylamine, or even DMAA. Two soldiers who employed the supplement died in 2011, which prompted the Defense Department to remove all products including DMAA from shops on army bases.

Even a current indictment against USPlabs, the Texas-based firm that produced the supplement, accused it of falsely claiming the product was made of pure plant extracts as it really contained synthetic stimulants made in China.

Earlier this season, the FDA remembered several supplements after they were found to comprise unapproved new drugs, and two more were remembered after they were found to contain unlisted anabolic steroids. In just the last week, that the FDA remembered certain supplements and liquid drugs manufactured by a firm called PharmaTech due to contamination.

“Consumers have no way to know that what’s in the tag is what’s really from the jar or vessel,” Austin explained. “There are several dubious businesses out there that are prepared to take a risk with consumers health and their lives.”